Geological Setting

Historical Exploration and Mining

Most small and medium scale Diamond mines are usually private family businesses which limits the availability of modern, published and reliable exploration and mining information on diamond deposits.

Historic information of the projects was mainly obtained through in-depth discussions with previous small-scale diggers and farmers and from consulting geologists who did work on the projects.

Large areas along the Vaal and Orange Rivers are covered by a very hard layer of calcrete, 0.5m-3m thick, which limits access to the underlying gravel horizons. The introduction of large modem earth moving equipment and drilling and blasting of the calcrete caps, and other technological improvements have resulted in some of the areas along the rivers being effectively explored since about 1996 by several Companies including Northern Cape Diamond Mining, Moonstone Diamonds (Australian), Pioneer Minerals, Gem Diamond Mining Corporation, Trans Hex, HC van Wyk Diamonds, Rockwell Diamonds, Bo-Karoo, KCME, DiamondCorp and Diamondcore Resources.

Trans Hex, a listed company which has very successfully mined alluvial diamonds for over 40 years, and other private operators like Sonop Mining (Chris Potgieter), Nelesco Mining and Schalk Steyn, have shown that alluvial mining can be successfully pursued.

Today virtually all the gravel resources between Douglas and Prieska are covered by means of mineral right application or existing mineral rights.

Alluvial diamond mining provides rapid start-up in respect of time to production, quick cash flow, capital and operating costs that are far lower than the costs of establishing kimberlite mines, mining equipment (earth moving fleets) and recovery plant that is almost all portable and mobile and diamond quality that is with few exceptions orders of magnitude higher than kimberlite diamond values.

Consequently, as a result of the above, there has been heightened interest in recent years in exploration support and investment for properly managed alluvial diamond producing companies. As the number of successful alluvial companies increases interest in this sector is likely to grow.

Background - Diamonds of the Kimberley Area

Despite having been the hub of the world diamond industry for over a hundred years, Kimberley remains the centre of one of the most exciting exploration provinces anywhere in the world. The Kimberley region is well known for its high-quality gemstones and is generally regarded as a priority target for the discovery of large stones. Extensive areas of terrace gravels flanking several important rivers have yet to be fully evaluated; and known diamondiferous kimberlite pipes and fissures await the application of modern mining and processing technology. Alluvial deposits in this region are well known for their high-quality gemstones, both in terms of size and quality, with a regional average value of about US$700 to 2,600 per carat.

Diamonds are known to occur in a variety of rocks, however the only known economically significant primary source of diamonds are kimberlite and lamproite. No significantly diamondiferous lamproites are known in South Africa where the primary sources mined are kimberlite pipes and dykes (also known as fissures).

Over 800 kimberlite occurrences have been identified in South Africa, but only 50 carry significant quantities of diamonds. Many occurrences are sub-economic due to the low grade or quality of the diamonds or the insufficiency of the size of the ore body.

Numerous significant diamondiferous kimberlite pipes are found in the Kimberley and Barkly West Districts. The nearest well-known kimberlites to the project area are the De Beers Kimberley Mines (now part of Petra Diamonds) and a number of smaller kimberlites including Kamfers Dam. These are all Group I kimberlites.

Numerous Group II kimberlites fissures occur between Barkly West and Windsorton, including those on the farms Harrisdale 226, Rosalind 224 and Holsdam 229. The nearest other Group II kimberlite mines are those at Loxton/Ardo and Bellsbank, which are situated respectively 40km, 90km and 130km to the northwest of At Last, De Bad and Lanyon Vale.

Alluvial geology of the Kimberley area

The erosion of diamondiferous kimberlites liberates diamonds onto the land surface, for redistribution by streams and rivers. The processes that lead to the deposition and concentration of diamonds in river sediments are obviously of direct importance in the formation of economic alluvial diamond deposits.

The South African alluvial deposits are distributed in a southwest-trending belt that stretches from the Limpopo River to the Namaqualand coast. The major deposits are concentrated along the Vaal and Orange River valleys and some tributaries of the Vaal River. The deposits invariably consist of gravel resting on Precambrian bedrock.

This bedrock contains trap sites for diamonds in the form of scour channels, potholes, gulleys and plunge pools, and in all cases, its competence and irregularity are sufficient to trap coarse debris that, in turn, act to entrain diamonds. The bedrock comprises a wide variety of rock types, including granite, gneiss, lava, dolomite, tillite, shale and quartzite, and cross-cutting dykes perpendicular to the fluvial channels and paleochannels are important in the development of trap sites.

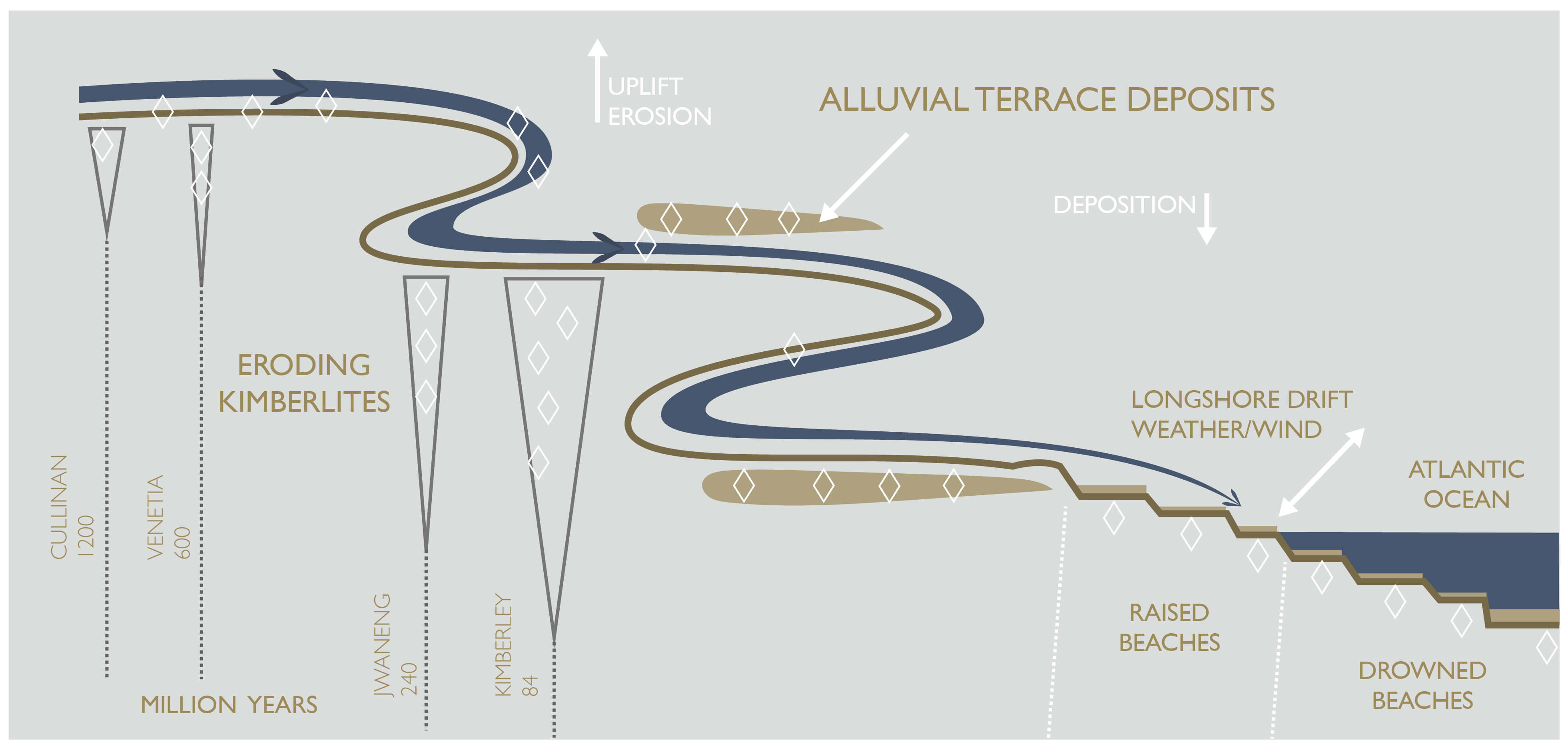

The diamonds were originally derived from kimberlites on the Kalahari Craton, mostly within South Africa and transported by rivers to their placer sites. Many of these placers were subsequently reworked during the Cenozoic and redeposited as younger placers in downstream locations as depicted in the schematic illustration.

The age of the alluvial placers ranges from Late Cretaceous to Quaternary with depositional peaks coinciding with fluvial phases during the Late Cretaceous, Miocene and Plio-Pleistocene. These ages post-date the emplacement of all the diamondiferous kimberlites on the Kalahari Craton from which the diamonds were derived.

Deposits of Miocene, Pliocene and Pleistocene age occur along the Vaal River valley between Christiana and Douglas and along the Orange River valley between Hopetown and Prieska. These deposits are located at elevations between present river level and 120m above present river levels. The diamonds were probably transported from kimberlites located near Kroonstad, Welkom, Theunissen, Boshof, Koffiefontein, and in northern Lesotho via former drainage courses of the Vals, Vet, Riet and Orange Rivers and a so-called Kimberley River that tapped the Boshof kimberlites prior to being captured by the Modder River during the Pliocene.

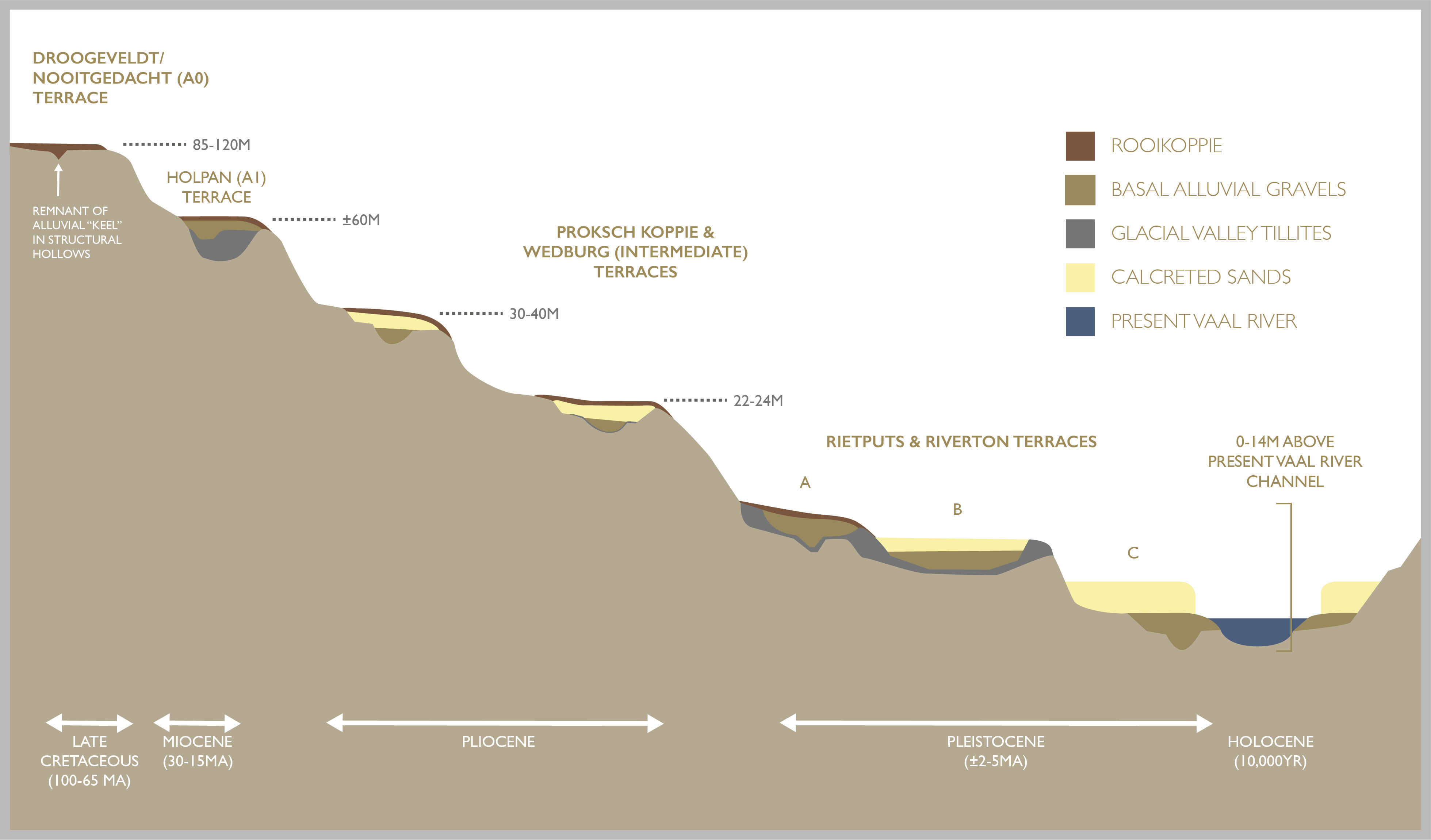

Studies of the Lower Vaal, Harts and Middle Orange River (MOR) alluvial deposits show that there are five broad phases of prominent alluvial deposit development in these areas reflected by several deposit types.

Cretaceous aged Nooitgedacht-Droogeveldt Terraces are considered to be the oldest alluvial deposits and they occur between 80 - 120 meters above the modem Vaal River S-W of Barkly West. These deposits probably conform in age to the initial period of late-Cretaceous uplift which triggered a period of accelerated river incision and simultaneous erosion and lowering of the land surfaces, accompanied by the supply of detritus, including diamonds.

Miocene-age Holpan and KIipdam Channel deposits occur at approximately 60 meters above the Vaal River. Younger terraces include the Pliocene-age Proksch Koppie and Wedburg Terraces, which occur at 30 - 45 and 20 - 30 meters respectively.

Pliocene - Holocene deposits or the youngest terraces, which include the current Vaal River channel, occur between 0 - 20 meters and are collectively referred to as the Rietputs and Riverton Terraces (figure 13).

Younger deposits, through a process of progressive weathering, deflation and winnowing of the above deposits, 'secondary' deposits known as Rooikoppies developed over large areas of the landscape. Typically these deposits are found to be broadly associated with older terraces and buried channels, these readily accessible deflation deposits were extensively mined by the old timers and Diggers. In many cases the presence of Rooikoppie deposits was useful in respect of highlighting the presence of older buried deposits.

Hundreds of thousands of carats and numerous large stones have been produced from these terraces at various projects with grades varying between 0.1 and 2.0 cpht.

Regional Geology of the Lower Vaal and Middle Orange River Deposits

Prior to the Karoo period, the (pre-Karoo) Vaal River cut a network of channels closely approximating the present floodplain. These channels were then utilized by the subsequent glaciers and were finally filled with Dwyka tillites and shales (at ±250 million years). The post-Karoo Vaal River, subsequently, incised into these formations and deposited gravels and large quantities of fine sediments.

The geological settings of the diamondiferous gravel deposits vary from thick remnant palaeo-river terraces and channels of late Cretaceous age through to young surface deflation or Rooikoppie deposits of 0.5 – 1.0 meters thick.

Through geological time, erosion and deflation of the very extensive primary gravel deposits lead to the formation of extensive lag deposits or Rooikoppie which in places were particularly rich. These deposits are generally associated with underlying primary gravels but mass weathering, material creep and movement of the heavier lag deposits down slopes has resulted in deposits which may be far more extensive than the underlying primary deposits.

Rooikoppie gravels have been extensively dug by the old-time diggers in the past, using unsophisticated mining and diamond recovery techniques. Highly fractured Ventersdorp lavas or Dwyka tillites underlie the Rooikoppie gravels. Iron has stained the entire assemblage, giving it a reddish colour and hence the name Rooikoppie.

Magmatic intrusions are in the form of Karoo-aged dolerite sills and dykes and Cretaceous-aged kimberlites.

In the Lower Vaal and MOR area dry periods lead to the precipitation of an extensive hard calcrete horizon which effectively defines the "interface" between the surface Rooikoppies and lower primary gravel deposits in many areas.

The calcrete prevented old time diggers from mining below the Rooikoppies and consequently large areas of primary gravel are being mined in areas such as the MOR by drilling, blasting and stripping the hard 1 to 2 meter calcrete layer and mining and processing the underlying preserved primary alluvial gravels.